One of my favourite Nigerian female authors is Buchi Emecheta. Her books have served as timely reminders on what happens to women if we fail to centre our needs and wants no matter what people may say or do.

Recently, I have been thinking of how Buchi Emecheta’s novels may be the closest things that serve as time capsules for Nigerian women of our generation.

For instance, her 1982 novel Double Yoke focuses on campus sexual harassment and is set in the University of Calabar.

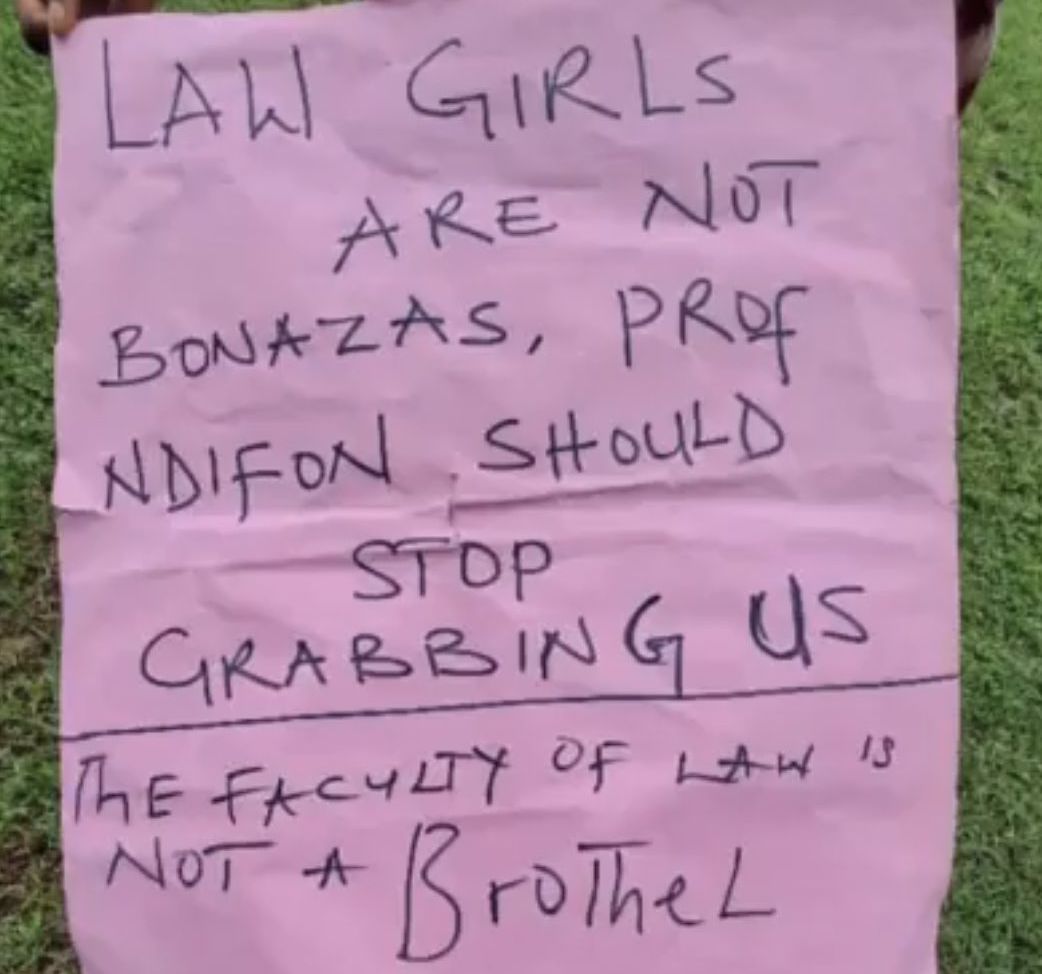

Ironically, the University of Calabar has been in the news for almost two months following a protest held by its female law students with them bringing accusations of molestation and rape by Professor Cyril Ndifon.

These protests led to the suspension of Prof. Ndifon and a panel was set up to investigate the allegations brought forward by the students.

The panel which was set up by Prof. Florence Obi who is UNICAL’s vice chancellor, included individuals such as Prof. Dorothy Oluwagbemi-Jacob – Chairperson; Dr. Brenda Akpan (Executive Director, Gender Development) – Member; Prof. Patrick Egaga (Director SERVICOM) – Member; Dr. Tony Eyang (Dean Students Affairs) – Member; Prof. Ayodeji T. Owolabi (Anti-Corruption and Transparency) – Member; Prof. Elizabeth Akpama (University Counselor)- Member and Barr. Gabriel O. Orok – Secretary.

There has been good news however. According to a report by BarristerNG, the panel found Prof. Cyril Ndifon guilty of gross misconduct, sexual harassment and issued a directive to him to refund three million naira that came from students paying him for a law journal which he never provided.

The panel went further to recommend that the “suspended Dean of law should face the statutory Disciplinary Committee of the University of Calabar for appropriate sanctions applicable to acts of both Major and Gross – misconduct”.

While it is commendable that some form of justice has come to the female law students of the University of Calabar, it is also important that all eyes remain on UNICAL to ensure that Prof. Cyril Ndifon faces the full length of the law and is not reinstated after this.

It is also important that as a society we question why women and girls are not safe from predators when we want to study at any educational level.

This is because Prof. Cyril Ndifon of the University of Calabar is only one out of several instances of women being harassed in institutions of higher learning across West Africa.

In 2019, a groundbreaking documentary called #SexForGrades was released by BBC Africa Eye. At the centre of it was journalist and filmmaker Kiki Mordi who is also a survivor of sexual harassment by lecturers. This documentary covered the predatory behaviours of lecturers in the University of Lagos, Nigeria and the University of Ghana.

Although the lecturers exposed in the SexForGrades documentary have been removed by their respective universities, the incident at University of Calabar points to the overall normalisation of sexual harassment in Nigerian universities.

If not from the lecturers themselves, sexual harassment and the lack of protection of female students from student to student harassment is still prevalent and mostly overlooked. For one, there is still the practice of older university boys preying after younger incoming graduates in the name of “October Rush”.

The normalisation of sexual harassment and grooming in Nigerian universities is also seen in boys “arranging babes” or outrightly telling their girfriends to sleep with a lecturer so that the boys can have better results. It is seen in non-academic staff like bankers and cafeteria workers harassing young women who come to eat.

Furthermore, in especially private religious universities, sexual harassment is normalised such that student pastors and leaders of fellowships can harass and rape girls with little to no consequence because they are seen as God’s anointed and so must not be questioned.

More often than not, young women are chastised for not aiming high and for not being ambitious with their dreams.

While I understand the thinking behind encouraging women to dream big, how do we expect women to dream big when your very existence in a place of learning is under threat? How do we expect women and girls to be confident enough to negotiate salaries, if in university, they had their courage stifled by male lecturers?

Especially by male lecturers so fearful of female ambition that they made it their calling to extinguish the bravery in young women as a requirement for them to graduate?

The reality is that so long as women are seen as inferior outside the classroom, any attempt to realise our full potential in the classroom will be met with scorn and disdain.

It is not enough that women have the right to education. That right is useless if women and girls are not at peace from violence while exercising that right.

Angel Nduka-Nwosu is a writer, journalist and editor. She moonlights occasionally as a podcaster on As Angel Was Sayin’. Catch her on all socials @asangelwassayin.